By Guillermo Montt and Glenda Quintini

The young psychology graduate working at a call centre or the mathematician making a fortune as a trader: we have all heard these stories or some version of them. But just how frequent are these situations and what are the consequences for the individuals involved is unknown?

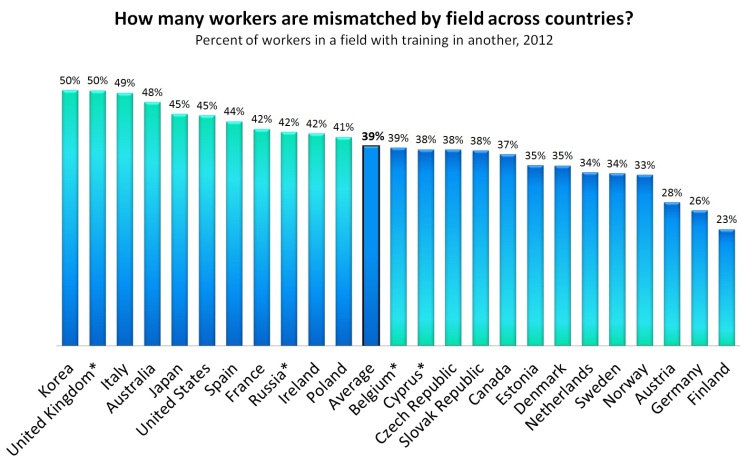

The new study released today “The Causes and Consequences of Field-of-Study Mismatch: An Analysis Using PIAAC” (Montt, 2015), based on the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012) finds that approximately 39% of workers in the 22 OECD countries and regions covered are mismatched by field of study – i.e. their highest educational attainment is in a field (e.g. health and welfare for a psychologist) that is unrelated to their occupation (e.g. services for a job at a call centre). Field-of-study mismatch is most common in Korea, England/N. Ireland (UK) and Italy, where almost half of dependent workers are mismatched. Graduates from certain fields are more likely to be mismatched: around three in four graduates from agriculture and veterinary and languages, humanities and arts are mismatched. It is also more likely to find mismatched workers in certain occupational groups than others: around four out of ten workers in occupations related to services or to social sciences, business and law graduated from fields unrelated to these occupations. By contrast, mismatch by field of study is least common in Austria, Finland and Germany; among graduates from the social sciences, business and law and health and welfare. It is also less likely to find mismatched workers in occupations related to science, mathematics and computing and humanities, languages and arts.

(*): See notes Figure 1 in Montt (2015).

These are the statistics but should mismatch by field be a concern for students, workers or policy makers? This is an issue that often generates animated debates between those who believe in the general value of education irrespective of the labour market opportunities it leads to and those who think studying should lead to a good qualifications and job-specific competences that are related to labour market needs. The paper by Montt shows that field-of-study mismatch is a problem when it leads to jobs in which a worker’s educational attainment is not recognised – i.e. a job for which the worker is over-qualified. Field-mismatched workers who are also over-qualified (around 40% of all field-mismatched workers) suffer a wage penalty that amounts to 25% lower hourly earnings when compared to graduates in the same field and with the same education level that are well matched to their jobs. These overqualified field-mismatched workers are, for example, those tertiary graduates who cannot find a job in their own area of study and have to accept a job requiring only an upper secondary school certificate in order to work in another field – the psychologist at the call centre. By contrast, in the vast majority of countries, field-mismatched workers who are not over-qualified do not experience a wage penalty. These are workers (e.g. a tertiary graduate from the science, mathematics and computing sector) that are able to find work in another field (e.g. social sciences, business and law) without having to downgrade – the mathematician working as a trader.

As wages reflect – at least partly – productivity, field-of-study mismatch when coupled with over-qualification can aggregate to substantial productivity losses for the economy because many workers’ skills are not put to their full productive use in their jobs. Costs can also arise when mismatched workers remain mismatched for their entire career, rendering part of their training not useful (a sunk education cost). Conservative estimates for 2012 point to a cost of 0.5% of GDP as a result of field-of-study mismatch, on average across countries, with peaks of over 1% of GDP in England/N. Ireland (UK) and Korea. This lower-bound estimate is driven mostly by situations in which field-mismatched workers are also overqualified for their jobs.

The study goes beyond incidence and consequences and provides some explanations for why over-qualified field mismatch comes about, suggesting possible policy solutions. In fact, a novelty of the paper is that it identifies two separate phenomena as being at the root of over-qualified field mismatch: on the one hand, workers’ inability to find jobs in their respective field because there are too many graduates in the same field (i.e. the field is saturated); on the other hand, the fact that their skills are not recognised by employers in other occupations (i.e. credentials are not transferrable across fields).

Several lessons can be drawn for both labour market and education policy. Correctly assessing the current and projected demand (saturation) for specific fields can inform career guidance and the determination of places available for each field. Enhancing transferability is possible through greater provision of general skills, through comprehensive qualifications frameworks that promote the recognition of skills across different fields, through competency-based occupational standards that focus more on the skills owned rather than the credentials earned, or flexible re-training programmes and active labour market programmes that allow workers to earn a credential in another field without having to undergo the entire programme.

For further details, contact Guillemo.Montt@oecd.org

Interesting study, essentially to compare the link between the mismatches and the salaries.

However the “penalty that amounts to 25% lower hourly earnings when compared to graduates in the same field and with the same education level that are well matched to their jobs. ” for over-qualified mismatches workers could be argued the other way around. Although with 25% lower hourly earnings. It could be argued that these people are still in a better financial situation / job position than if they hadn’t the chance to be promoted, in a country where mismatches were less tolerated.

Finally it’s interesting to note that usual “good students” countries for other factors (happiness, health, etc.) such as Sweden, Norway, Finland, Germany are all having the lowest mismatch percentages.

LikeLike

Hello,

Indeed, the picture is somewhat different when you compare mismatched (over-qualified) workers in the job with those that are well matched in the job. Over-qualified workers earn more than the well-matched doing the same job, the extra qualifications make them more productive. Hence the incentive for employers to hire over-qualified workers; but this doesn’t necessarily mean it’s an incentive for the economy as a whole. However, this premium is much lower than the penalty over-qualified workers suffer when compared to workers who are well-matched and have their same qualification.

And the point you make about the “good students” signals the interrelationships in skills policies and outcomes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Guillermo and Glenda,

Thank you for the research and analysis. Really interesting.

First, wasn’t the data available regarding Chile?

Second, in general terms you state that this mismatch is negative because a group of professionals are under-paid. What would you suggest in terms of public policy? Should a government promote further alignment between type of bachelor’s degree and type job? What about those cultures based in college type of education (i.e.: US) vs those more specific (i.e.: Germany). Finally, there are experts out there saying that to follow a career in business or even sciences young people should study literature, English or arts to get qualitative skills before getting the quantitative ones. Would not this produce a “natural” mismatch?

Kind regards,

Cris Caorsi

LikeLike

Hola Cristóbal,

We are on the process of collecting data for Chile. On July 6, 2016, we will publish the PIAAC Second International Report, including the levels of field-of-study mismatch for Chile (and 8 other new countries) and any relationship to labour market outcomes. This report will also give a comparative assessment of Chilean adult skill levels in literacy, numeracy and problem solving (similar to what we published in 2013 in the PIAAC first international report: http://skills.oecd.org/OECD_Skills_Outlook_2013.pdf).

What we find is that mismatch is negative when it leads to over-qualification. In this situation, professionals are usually underpaid, their skills are not put to use to their full potential and, on aggregate terms, the economy operates with a lower productive potential. What is interesting, though, is that overqualified workers are usually more productive than their well-qualified peers doing the same job: firms have an incentive to hire overqualified workers, but as a whole the economy is less well-off when this happens.

As for policy lessons, there are several; many of which are particularly relevant in the Chilean context.They point to both allowing for greater alignment between the supply of skills and the demand for skills but also more flexibility to allow for workers to move from one field to another (which implies employers recognising the value of skills from other fields).

For one, countries can invest in information systems to better guide the offer of educational programmes (e.g. skills anticipation systems to better co-ordinate the number of graduates with labour market needs). Programmes that allow for workers to re-train while not having to undergo full training is another option. Developing qualification frameworks and occupational standards that recognise that workers from other fields have the skills to perform in other sectors is also relevant – and true, given that those workers that are able to work in another field without downgrading their qualification do not suffer a wage penalty.

The natural mismatch you mention is by no means problematic. Many countries are currently discussing not whether to eliminate mismatch, but what is the desirable level of mismatch. We do not believe mismatch per se is problematic, it is when it leads to lesser opportunities for graduates and workers because their skills are not recognised (leading to lower wages and productivity).

All the best y muchos saludos,

Guillermo.

LikeLike

“Many countries are currently discussing not whether to eliminate mismatch, but what is the desirable level of mismatch”.

Thanks Guillermo. Nice phrase. Quite a challenge countries have to identify the desirable level of mismatch though.

Kind regards.

LikeLike

Hola Guillermo and Glenda,

one question, which are the 8 new countries in PIAAC?

LikeLike

Hola Jaime,

Chile, Greece, Indonesia*, Israel, Lithuania*, New Zealand, Singapore*, Slovenia, Turkey (actually 9 countries) will have their data published on July 6, 2016.

You can find more information about the study in http://www.oecd.org/site/piaac and http://www.oecd.org/site/piaac/surveyofadultskills.htm .

All the best.

Guillermo.

(And sorry for the late reply, we are just beginning to understand the different parts of this platform).

LikeLike