By Fabio Manca.

Recent empirical literature warns about the negative impact that skills mismatch can have on individuals and economies as a whole. At the individual level, over-qualification and over-skilling entail lower earnings, lower job satisfaction and a higher risk of unemployment relative to well-matched workers (OECD, 2015 (forthcoming); Quintini, 2011). At the aggregate level, skill and qualifications mismatch are associated with lower labour productivity within industries (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2015)

Skills mismatch is painfully widespread. As an example, 23% of workers across EU-27 countries are employed in occupations for which they have either more or less education than required by their job (Figure 1).

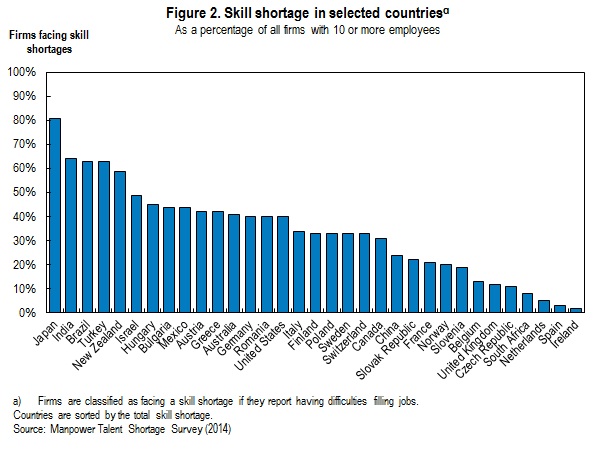

Strikingly, despite the high incidence of over-qualified workers, many employers are not able to find the skills they are looking for in the labour market. A recent survey of more than 40 countries (both European and non-European) shows that 36% of employers (on average) find it difficult to fill specific vacancies due to the lack of adequate skills (Figure 2). The biggest ‘skills shortages’ are found in the skilled trades (e.g. welders, electricians and machinists), engineering and technicians.

Skills shortages emerge also in countries with high unemployment rates. In Greece, for instance, more than 40% of employers struggle to find workers with the ‘right’ skills.

The reasons behind this phenomenon are multiple. In some countries, for instance, training systems lag behind the rapidly changing demand for skills. In others, upward trends in average educational attainment are unmet by the demand from the labour market in the short run.

To a certain extent, skills mismatches and shortages are natural phenomena. No-one can know with certainty what her/his career will be. Personal interests and ambitions can change, as such, career paths. Short periods of mismatch are likely to arise in those cases. This said, the extent and persistence of skills mismatch across countries varies dramatically, hinting to the fact that countries may differ in their ability to develop a coherent policy response to address prolonged and ‘unwanted’ periods of skills mismatch.

A sound policy response is usually based on robust evidence-based information, and tackling skills mismatch is not exception to this principle. ‘Skills Assessment and Anticipation’ (SAA) exercises have been developed in virtually all OECD countries and are generally led by National Ministries, Public Employment Services or Statistical offices. These initiatives aim to produce reliable ‘labour market intelligence’ on what skills are (or will be) needed in the labour market and to anticipate whether the current (or foreseen) supply of skills will be able to cope with this demand.

SAA exercises vary in their scope, methods and characteristics and, as such, in their effectiveness. Surveys to students and employers, measuring skills supply and demand respectively, are some of the most frequent tools used to diagnose the presence of skills imbalances in the current the labour market (OECD, 2015 forthcoming). Economic models are also built (usually by national Statistical Offices) to forecast potential skills imbalances and to plan a policy response to these challenges in the medium to long-run.

While skills information may be out there, what really matters is how this information is used. Results from SAA exercises feed into education, employment or migration policy by informing, among others, the design of education and training programmes, that of hiring incentives for workers with specific skills needed in the labour market or the development of programmes to attract talent from abroad.

Similarly, SAA information plays a crucial role in informing students and jobseekers on what their chances of being employed in certain occupations, carrying out certain tasks or using certain skills will be in the future. This information can have crucial implications on individuals’ choices to invest in education, take on training or move to another region or country, eventually limiting the likelihood of skills mismatch.

Skills imbalances, in fact, can be geographically localised and more severe in certain regions than in others. Local surpluses of skills can arise, for instance, as a consequence of the offshoring of certain economic activities. In many OECD countries, SAA exercises tend to provide information at the regional and local level to prompt a better planning of financial resources devoted to the design of active labour market policies (e.g. retraining and on-the-job training programmes and the job-matching activities of local Public Employment Service offices) tailored to the needs of workers of specific areas or economic sectors. SAA exercises, therefore, can be a powerful ally to both regional and industrial economic planning.

Several obstacles, however, can limit the effectiveness of SAA exercises in reducing the extent of skills mismatch. Reaching a wide audience that encompasses not only policy makers but also students, job-seekers, employers and workers is, for instance, an open challenge in many countries. The interface and the language used to disseminate the skills information needs to be tailored to a constellation of different users and uses for them to fully reap its benefits. Some countries are still lagging behind in this respect. The use of new media channels or social networks is not widespread. This latter, however, could help fill the gap between labour market information (sometimes abstract and obscure in nature) and a wider audience of final users, potentially playing a crucial role in education, employment and (even) migration decisions and reducing the incidence of skills mismatch.

Cover photo credits: ©Shutterstock.com/Andrey Burmakin

Thanks for the blogpost – it makes for an interesting read (along with this other one: https://goo.gl/mOjzga ).

It comes as a surprise though that you don’t mention data coming from online job postings/ads as a potential source of useful information for SAA exercises. The analysis of live job postings can tell us what are the skills/roles most in demand today, allow us to build trends of employer demand for specific skills/roles and potentially develop predictions of future needs, as well.

Through the analysis of job postings, we can also observe what are the skills and roles that are most spread across different sectors/occupations – i.e. most “transferable”. In the presence of imbalances/displacement across different sectors/industries, job seekers possessing such skills will also be the ones who can more easily switch sector/field reducing the overall incidence of mismatch in the labor market.

Would you agree with this?

LikeLike

Dear Mariano,

You are right. Data on job posting and vacancy surveys can be very useful sources of information. These are used in some OECD countries to assess current skill needs. In Sweden, for instance, the Public Employment Service is developing sophisticated tools to collect information about a broad range of skills from CVs uploaded to their system or from job vacancies posted by employers. This kind of data has, however, limitations as they may not be always representative of the whole labour market and should be treated with caution when making inference on general labour market trends.

LikeLike

Thank you for your important and on-going research. One factor that you did not mention is the mismatching for working mothers due to their desire to have more flexibility and less stress in their jobs. Does your research take account of this voluntary acceptance of lower paid jobs for which many women are significantly overqualified? Is there specific policy advice directed at this work-family balance issue as related to skills match? I’m curious about this, being a working mother of three myself.

LikeLike

Good points Julie! Although family constraints/commitments are potentially a good reason behind mismatch, only few studies have actually found that marital status or child care responsibility affect the likelihood of being mismatched. The paper we discuss in this blog does not address this but we have done other work on the subject where you can find some material around this issue (see here for some analysis

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kg59fcz3tkd-en

and here for a literature review

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kg58j9d7b6d-en)

LikeLike